the back brain is an unnamed thing

I have been thinking a lot about what Lucy Sante calls the “back brain.”

…many writers are procedural or mimetic or discursive. They are raconteurs or reporters or haranguers or intellectuals. They employ front-brain operations to render a story or an idea into words, translating straight across from one to the other.

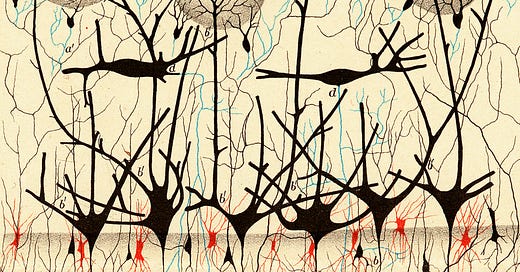

Meanwhile, back brain writers rely on something “unconscious, instinctive, libidinal, maybe extrasensory.” They don’t quite know where they’re going. It’s not that Sante is saying we are using the cerebellum, brainstem, and occipital lobes to write. It’s more that she’s referring to a process that feels less conscious than semi-conscious.

At first, the back brain sounded to me like a lot of other literary writing advice. Wishy washy. A little tinged with new age, it’s-approximately-this-but-I-can’t-prove-it vibes. Then, I wrote some more, and suddenly the abstractions started to make sense.

I think is because the role of the observer in our world has been understated. It’s often treated as something esoteric. You know, the type of person who used to mulch around in a forest, spot a small yellow frog with a mushroom growing out of its side, and jot down an illustration, which researchers would then extrapolate from.

I don’t think the observer gets much credit these days. It’s not that I think folk knowledge should dominate the very important work of scientists and institutions. But I think we don’t always take the observations of people working in a field, at a craft, very seriously.

Which is why I’m going to take this back-brain thing seriously.

a theory that extends well to intuitive writing

Imagining the back brain has helped me a lot with fiction. Especially with plot. I’m talking, of course, about literary fiction in the Western tradition, and not genre fiction or writing as if I’m from some other country.

I used to try and lay plots down before writing something, and would find myself with some cliched set of actions that had already been stamped in my mind from some previous text, movie, myth.

Not that I think there’s anything specifically wrong with writing this way. Some people can arrange this front brain work beautifully, and create intricate, meaningful stories that move past their own obvious mental scaffolds. But I’ve found that this practice doesn’t work for me. It never leads me somewhere unknown, which is the primary reason I write fiction.

Of course, I don’t think that the back brain is any purer than front-brain writing. I just think I can’t see the influences, which makes it more enjoyable and more of a mystery.

A while ago, I read an essay by Brandon Taylor that I can’t find now. In it, he says that one should learn craft very granularly, very slowly, and very well so that it is possible to go very fast afterwards. I think this is something that great back-brained writers do well. There’s a fluency to their semi-conscious writing. They’ve spent the front-brain time practicing and integrating rules so that the back brain can move around in its dark room elegantly.

I actually think it’s even harder to become a good intuitive writer who can write plot. As in, an intuitive story where something happens in an organic but unique-to-you way. In fact, I’m willing to say that good back-brained writing requires plot, specifically because back-brained decision-making about things that happen in a story leads to really inventive and strange circumstances.

This is not to say that the back brain is some magical part of the mind that is only accessible by Genius. I just think there are many ways in which we interact with language that we have yet to understand, and that is precisely why talking about back-brain writing sounds so mystical.

especially in an internet of heavy non-fiction

I wonder how much of my taste is influenced by the times. Some plotty, systems novels really work for me—I’m a fan of Hari Kunzru, for example.

But the internet has changed how I experience facts. Wherever I go, I’m up against facts, or things purporting to be facts. That’s what people on the internet are always doing, or claim to be doing. The language is discursive, argumentative, attempting to prove a point, and even when the person who is producing it knows that they’re lying, the form necessitates that it masquerades as the truth.

There’s an entire genre of TikTok accounts that come up with absurd lies that go viral—that time I knocked my teeth out in front of my high school crush and projectile-sprayed blood all over his nice white t-shirt, and it was picture day at school so he was forever marked with my specimen.

This is a personal experience. I know that others have found their way into internet fiction—Wattpad, creepy pastas, and the like. I might be convinced to change this opinion in some future. But it hasn’t happened just yet. And because of that, fiction online occupies a very weak position online for me. When I enter a short story on my browser knowing that it’s fictional, I don’t take it seriously.

However, I do take fiction seriously within the confines of a book. Maybe it’s because I’m used to the form of a novel and I come to it with certain expectations that I’ve already been made familiar with.

Which is why front-brain-dominant literary fiction—in which writers don’t integrate facts well with their stories, in which facts hang around a story like rigid data—doesn’t work well for me. It distorts what I’ve come to desire these days from literary fiction, which is a story told from the intuitive, sense-making back-brain. I want my fiction to be factual, but I don’t want it data-driven or studded with facts. I don’t want the narrative to follow a story that can be made up by gathering various data points from dusty corners of the internet. I want to read something that is created from the back, the as-yet-unobserved.

I’m reminded of the dictum writers say so often—that half of writing is “not writing.” It’s eating, sleeping, dreaming, breathing, procrastinating. What is happening all this time is back-office stuff, as Sante puts it.

Nevertheless, if you’re fully signed up to your project, are tackling the research and asking the questions, important clerical work will be occurring in your back brain. Your chapters are being reorganized as you sleep. Your internal editors are busy sorting wheat from chaff. To benefit from this mighty internal mechanism, you just need to trust in it.

as exemplified by denis johnson

Here’s an example of the back-brained stuff I like, so what I’m saying feels less esoteric. From Denis Johnson’s The Name of the World, which I read recently and enjoyed.

It starts off with a very small frame, in which the protagonist, who is a middling, middle-age academic in the Midwest, tells us he feels excited to go to dinner at a well-regarded professor’s place, because it was the sort of thing he always dreamt of doing. He’s yearned for this moment ever since he saw it in a movie.

As the story goes on, you learn that the protagonist has lost his wife and daughter, and hasn’t been able to move past this grief. This stuckness is never made explicit, but the plot points get lodged in some stew, and then, eventually, a few surprising and natural moments start to loosen it.

The ending—which Patrick Nathan commented “sort of walks away from itself in the end, when normally his final paragraphs love to turn the blade”—leaves something to be wanted. But you still get the sense that the book isn’t moving towards a planned resolution. Instead, it feels like you are watching the narrator paint, and by the end, they will step away from that canvas, so you can observe the shape of the grief he’s been painting.

That is a well-crafted, back-brained plot. It doesn’t feel like it’s being driven anywhere by the writer. But it does end up somewhere internal, intuitive, natural, unique.

Read a section!

“...it wouldn’t be claiming too much to say that as I sat there holding in my fingers Mr. Hicks’s list of head-injury victims I felt the stirring even of parts of me that had been dead since childhood, that sense of the child as a sort of antenna stuck in the middle of an infinite expanse of possibilities. And childhood’s low-grade astonishments, its intimations of a perpetual circus… meeting at random, kids with small remarkable talents or traits, with double-jointed thumbs, a third or even a fourth set of teeth. I don’t claim I enjoyed those long-ago days very much, they were so full of ridiculous horrors, but there was also this capacity of the universe to delight by turning up, like a beautiful shell on a long empty beach, a kid whose older teenaged sister liked to show off her bare breasts, or a boy who could take a drag off a cigarette, pinch his mouth and nostrils shut, and force smoke out through his ears. What happened to them? The boy whose hands were an optical illusion. His hands looked reasonably proportioned and complete, they were unremarkable until you looked closely and discovered that each hand had only three fingers, plus a thumb. But if you asked me, “Which finger was missing?” I couldn’t have chosen. All his fingers seemed to be there.

This is really motivating, Meghna! I’m becoming more comfortable—no! more in search of!—leaving a reader with a painting rather than a resolution. I really loved that characterization. I’ve been taking a class about dreams (a very back brained activity) and this helped me connect some dots as it relates to writing. Great stuff. Thank you!

really dug this, thanks