Hel-lo,

I have a new column on New York with India’s The Print, soon to be bimonthly. For my first, I wrote about the India-Pakistan cricket match taking place in Long Island in June, a blockbuster of an event, the first of its kind in the U.S. Here are just a few of the wild details: for the purpose of the World Cup matches, a $30 million, 34,000-seater stadium will be erected in a month and taken down a month after. A purported three million people have signed up specifically for the India-Pakistan tickets. And the remaining tickets have migrated to StubHub and run between $1400 and $70,000. Taylor Swift prices, the buzziest event to ever come to this little elbow crease of Long Island.

I wrote about a worry I had. While the event might push cricket out of the shadows of New York life and into the huddle of baseball, basketball, and even soccer, it might shrivel up a delicate part of our city, a cricketing culture that has developed after work out of a love for the sport, old nationalisms left to the side.

But after I published my column, I started to question this worry. There’s this filter I tend to see the world through, that the small and the old is better than the new and growing.

The new and growing, certainly, is what Manhattan is about these days. Within the small, pearly clutch of Flatiron streets, a new weather-resistant sculpture has emerged, a portal with a screen that connects to a sibling in Dublin. Send a kiss in Manhattan and it lands in Ireland. Or pull your pants down, send a gang sign, wink at someone cute. Don’t go too far—this week, the Flatiron portal shut down briefly after a phone in Dublin was lifted to its camera, first showing an erect penis, then 9/11, then the George Floyd murder.

But this isn’t exactly new. It is the spirit of the late Omegle rising once more. Omegle was one among a few stranger-to-stranger video sites that lurked throughout my teens and college years. Just hit next and match with strangers, most often men flashing genitalia. Still, the site—a roulette of empathy—was part of what had made me so rah-rah about the old internet. Once you figured out how to avoid the meat, you could get to its real beauty, asking strangers how they felt, what they were thinking about, whether they were happy.

And this isn’t just me being a ye-olde-millennial, some broken record of old internet nostalgia. Omegle surged in popularity during the pandemic, driven by bored-at-home teens looking for a little wind-in-hair risk.

Still, last year, it was shut down by founder Leif K-Brooks because he couldn’t afford to solve the platform’s crisis of pedophilia. At the news, I felt a strange emotion that triangulated around “loss.” But not quite, also something more complex.

Where does one draw the line between nostalgia and apology? Between what something can be and what it really is, between its potential and where it actually lands?

“Were the porn theaters romantic? Not at all. But because of the people who used them, they were humane and functional, fulfilling needs that most of our society does not yet know how to acknowledge.”

That is Samuel Delaney in his memoir/critical essay Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, in which he laments the loss of the porn theaters that splayed across Times Square in the 60s. Seedy, dirty places where he hooked up with mostly men—strangers, acquaintances, and long-time lovers across all sorts of demographics. Not just hooked up. Grew to care for, helped move homes, worried about when they didn’t show up.

Humane and functional, fulfilling needs that we don’t yet know how to acknowledge. What are those needs? Simply, “that we speak to strangers, live next to them, and learn how to relate to them on many levels, from the political to the sexual.”

Unfortunately, speaking to strangers through a piddling site like Omegle, which only halfheartedly tried ads and subscriptions, is expensive on today’s internet. Meta has set the standard for content moderation, spending $5 billion on “safety and security” in 2022 alone. In turn, it has removed huge swathes of content it deems unsafe and has set a high bar that is challenging to adhere to. (This is a good game to better understand how hard content moderation is, if you’re interested).

Having an account linked to an email or a phone number, for one, is a near non-negotiable on today’s social internet. Omegle never tried it. It would have ruined the free, wind-in-hair feeling of meeting strangers, like getting your ID checked before showing your face on the Flatiron portal. More likely, it would have been too much work for the founder, who started the website at 18-years-old, in 2009, and seems to remain deeply surprised by its growth.

Again, there is a line between nostalgia and apology, between what a thing could have been and what it actually is. I read through some of the cases that Omegle had against it. They were startling and impermissible. I almost forgot about what was good with the platform.

But let’s not forget that there is such a thing as a portal.

I looked into one in 2006, during an India-Pakistan match that we streamed in over a flat, round DISH satellite installed on our roof. The resolution was choppy and the game stalled often. This was before the new T20 format had emerged, an abbreviated innovation on cricket that runs for just two-and-a-half hours and is meant to attract younger fans.

The match was endless. I fell asleep and woke up several times. More interesting to me than the polite claps and wide, meditative shots of the same length of pitch were my parents and their friends, who cheered and jeered as the match went on. Then, when India lost, they called their Pakistani friends and wished them well.

Here’s another portal: With the match, India’s Virat Kohli (who has the same amount of Instagram followers as Ms. Swift, around 280M) will play for his first time in the U.S. His fandom is particularly obsessive. Virat Kohli masks have been spotted at past cricketing events. Other Kohli-lovers have turned their talents to generative art, like one viral image of a child making sand statues of Virat.

My favorite piece of ephemera was set in an uncharacteristically clean Times Square, through which Virat is pulling his luggage. When I brought up Virat with a Pakistani friend, she admitted that she was planning to watch the India-Pakistan match just to cheer him on. And what mattered more to her than who won was seeing Virat

I have wondered if there are more portals I can look for, less about small and old or large and new, rather different angles that might mean “hope,” where what is good and unarticulated isn’t dead, and is instead lurking in wait of the right moment.

We could also just build this portal:

(btw, Coca Cola tried this in 2013)

A few weeks ago, a pro-Palestine encampment emerged at my alma mater Stony Brook University, a state university on Long Island. This was a good interview with Josh Dubnau, a tenured professor of anesthesiology and neurology, who recounts the event and conjectures why the largely peaceful protesting students were arrested. Dubnau’s theory is an interesting one. He believes that Stony Brook’s ambitions as a business have eclipsed any classically academic ambitions of free speech and open discourse it may have had; last year, the VP of police was given the job title of “VP of enterprise risk management and chief security officer.”

“They assess risk, and free speech is risky. Because if the free speech is a type of speech that the governor has said is wrong and labels as antisemitic, even though it's not, then that speech according to the risk assessment is a threat to the corporation.”

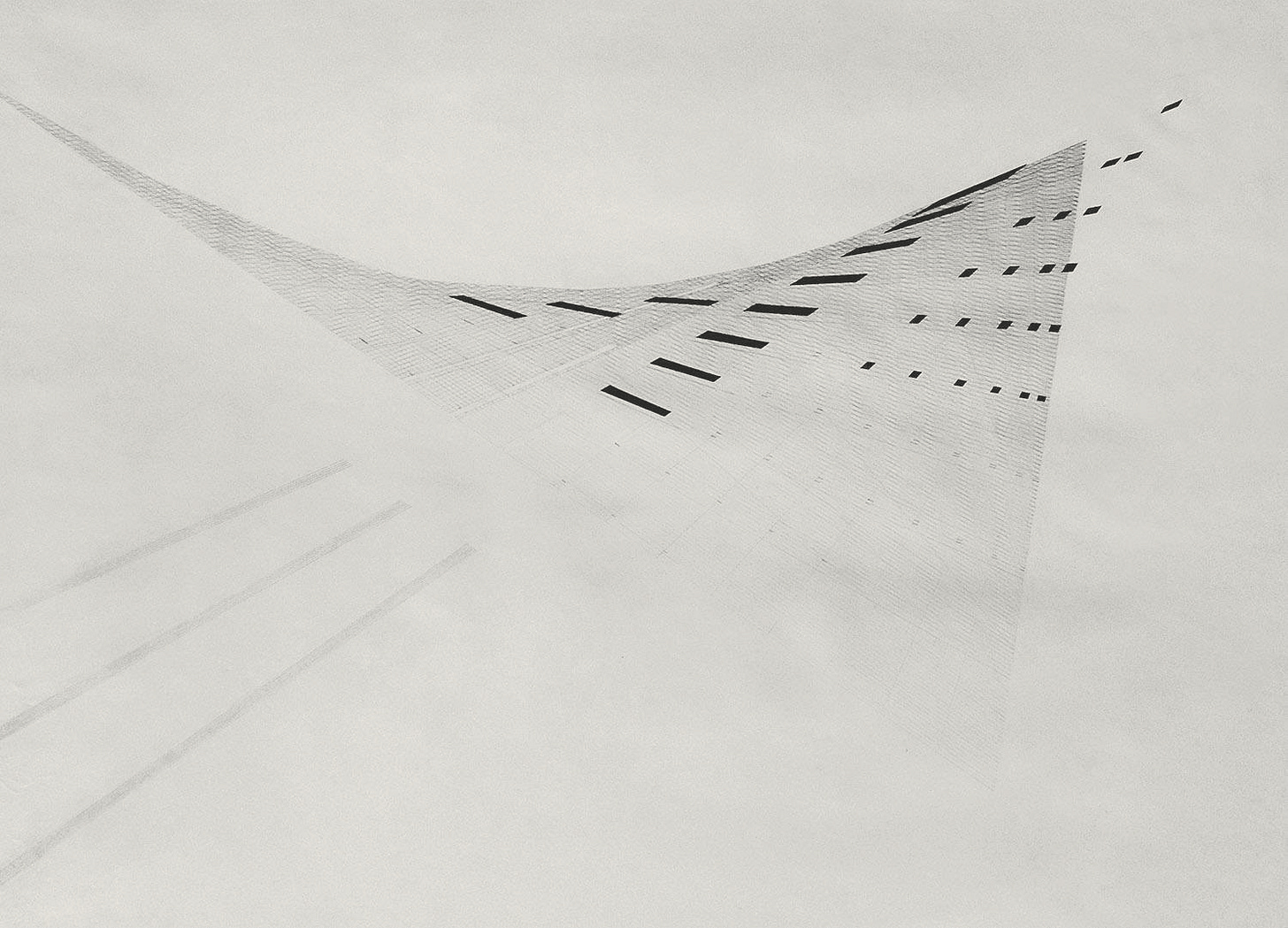

Untitled by Nasreen Mohamedi, born in 1937 Karachi, then India, now Pakistan: