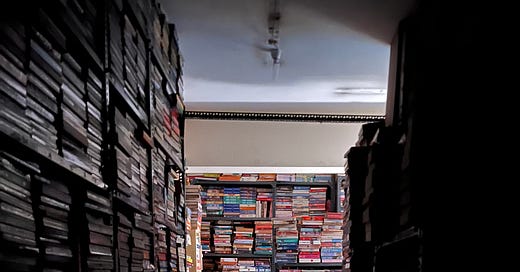

Taken at Blossom’s, a bookstore in Bengaluru (2024)

At least four of these books were found on sidewalks around Brooklyn, along with several others that didn’t make my list. At my last apartment, I used to find mostly galleys, which made me believe that I had a neighbor who worked in publishing. I would see Sanmao propped against the black railing that wrapped the oak in front of my house and think—well, that’s nice of whoever-this-is. But I recently found Hilton Als laid out fresh on a step near my new apartment. He was above a frayed book about Scrum Management, which made me even more suspicious. So now I have a theory: There is a plot to get people to read more by leaving books out on sidewalks around New York. Whose plot it is, I can’t say. But it’s not the worst idea.

My 14 favorite books of the year… and a bonus of three short stories at the end if you get to it.

The House of Mirth, Edith Wharton (1905)

Chronicles the life of Lily, a once-rich and very beautiful woman who lives in Gilded Age New York and is pursued by various wealthy and hungry suitors who can help her break out of her class. Unfortunately, she finds that each chance is ruined because of the conflict at her heart; does she want to find real love and meaning, or does she want to marry some corrupt or unattractive man for money?—money, which will allow her to showcase her beauty and get her the chance to attend tableau vivant parties where hired nymphs dance like Boticelli’s Primavera. All of this questioning happens as she develops wrinkles and watches her chances wane apace.

Impossible to put down. Good for fans of Sally Rooney, because Wharton, who initially published this as a serial novel over twelve installments, is an expert at keeping people hooked, following near-wins with losses, then worse losses. Like Rooney.

After this, to understand more about the Gilded Age, I read Hernan Diaz’s Trust, a very sharply-constructed and gorgeously-written book. Unfortunately, I found Diaz’s book lacking in a way that’s often typical of fiction—its descriptions of the financial world felt abstract, and material realities were sacrificed for poetic large numbers, and that all felt too far-away for me to understand the world they lived in.

Wharton does a good job with this, probably because she is limiting herself to smaller-scale specific conditions that tell much larger stories, including a particularly compelling scene with a guy who promises Lily he is investing her money to get her big returns. He does get her big returns, but they turn out to be from his pocket, because he’s trying to sleep with her.

The Pornographer, John McGahern (1979)

Beautiful book. Warm and intimate. Written in first-person. A surprising, wonderful find. Read if you want to tear through an urban read that is constructed fully around feeling.

The main guy can’t settle down, lives alone and doesn’t know his neighbors, writes pornography. I imagine McGahern was describing a certain modern, atomized listlessness that was entering its heyday in Dublin of the 70s, one that feels almost obvious today. The book progresses alongside a woman who does want to settle down, and the interiors of the characters were so roomy I felt like I could move around in them. The story is written mostly in dialogue that has been pored over, with excellent character tics and rounded words to denote class.

This book ranks high for me on my most important fiction metric, what I describe to myself as the Humanism scale, which means it excelled, above all else, at depicting the strange and beautiful and slow contours of being a person. The sort of thing that makes fiction worth reading, the sort of book that makes fiction worth writing.

American Abductions, Mauro Javier Cárdenas (2024)

A book that is like dipping your hand into a river of data. Set in some future that feels a few steps ahead of ours, each chapter a long, run-on sentence that follows a family that has been separated after their father has been deported from the U.S. back to Colombia. Some choose to return while others stay, but they all replay the act endlessly in their minds, and many times the boundaries of who the abduction has happened to collapse. It’s a poem and a work of fiction put together. Absurd, hilarious, magical, dark. Each chapter is a discrete story. I generally don’t find that experimental works do it for me, which is why this was surprising. Each line had so much in it that I really had to focus while reading.

I also enjoyed the characters a lot. The deportation, the trauma—it doesn’t overwhelm their humanity, that is to say their weird quirks; mothers continue to be guilty about sons, question whether what has happened is reality. And all in-between are a million references that have an information-age way of thinking, like someone put a recorder right up to their brain and recorded the way they bubble and double back.

I read this good interview with Cárdenas. …“natural language processing algorithms were developed in Python to power my Leonora Carrington talking car…Hypothesis: the only truly experimental literature of the 21st century is that which plays with algorithms.”

TBH, dragged. “I’ve been mocking traditional realism for so long that it feels too easy to continue to put on that variety show. For instance: hey you’re replicating the same narrative conventions that companies have repurposed so you’ll purchase their cures for your corns. Or: so you wrote another poetic pantomime of your suffering, eh? Or: how come your style is tied to the tenure requirements of the University of Southern Corn?”

Minor Detail, Adania Shibli (2017)

A two-part novel, lent to me by a friend, translated from Arabic in 2020. The first part is about a woman who is raped and murdered in 1949 Palestine, told through the viewpoint of the officer, whose life is repetitive with routine until the violent act happens. The second is in first person, current day, about a woman finding and hunting this story down in search of some vague, unverifiable sense of the truth, a woman who struggles to leave her home as she thinks about the borders around her.

This is a difficult book to read and very difficult to write about. It is intense and devastating. I have been thinking a lot about how plot is influenced by what feels possible in an environment, how the same plot in the U.S. would seem dark and intense, but set in Palestine, it feels devastatingly realistic.

Rejection, Tony Tulathimutte (2024)

Ridiculous and perverted and intelligent. The sort of book that will make you want to hide your face while you’re reading it. What I’ve always enjoyed about Tulathimutte’s writing is that he is willing to say embarrassing and frank and sometimes vile things, but he does it all without being reactionary.

Two of his pieces are online: the original The Feminist, which was the first time I’d heard of him. After that, I took Tony’s CRIT class and really learned, for the first time, what craft means and why it matters.

The second is Ahegao. Don’t read it at work.

Second Place, Rachel Cusk (2021)

An epistolary novel—written in the form of a letter—that includes the most wicked and fun character I’ve encountered in a long time. I read this book as a question of what it means to let the devil into your home. What makes this villain compelling is that he is somewhat shabby, which is a quality I tend to see as harmless compared to the aggression of youth, but this shabbiness is the place where he stabs from.

I really, really loved this book. The book weaves between dialogue—several bits of it made me put down the book in shock, seriously—and a confessional tone. Here is a sample:

“For the first time, Jeffers, I considered the possibility that art—not just L’s art but the whole notion of art—might itself be a serpent, whispering in our ears, sapping away all our satisfaction and our belief in the things of this world with the idea that there was something higher and better within us which could never be equalled by what was right in front of us. The distance of art suddenly felt like nothing but the distance in myself, the coldest, loneliest distance in the world from true love and belonging.”

Em and the Big Hoom, Jerry Pinto (2014)

The pages of this book are trimmed with a deep purple, and I had seen it earlier this year at Blossom’s earlier, a bookstore in Bengaluru that I used to love that now feels like it has been hollowed out; the table out front looks like no one has read a book in a decade, and much better books can be found at the tree-lined Champaca Books, or at any of the new large, well-lit bookstores on Church Street. But I picked up this book because I recognized Jerry Pinto’s name, from when I had seen him in the 2010s at the Jaipur Literature Festival, speaking as a translator of Cobalt Blue (an old favorite) from Marathi.

It is a first person book written by a son, who tells us about his mother Em and her mental health issues. A small, strong book set in Mumbai in the 1960s. About how to love someone when cures—or conversations—are culturally taboo. Em is classified as “mad,” but is loved anyway. The type of book you buy, leave in your bookshelf, and pick up one day when you are looking to feel something.

Technics and Civilization, Lewis Mumford (1934)

A Queens man, au natural. And a graduate of my high school. A brilliant, eternally fresh book that traces the machine through society. Mumford will tell you how the clocks of 13th century monasteries were responsible for creating how we hold, calculate, and partition off time today, that these clocks turned time from an entity that was perhaps an atmosphere into an object. Then, he will tell you how the clock cleaved society and how we adjusted to it; the bookkeeper, the work schedules, the rhythms in the factory. And he will do this for every technology up until 1934, when radios and telephones began to manipulate distance.

What makes Mumford fresh is his thesis about machines, which is that we should never allow them to overwhelm us, that machines should always add to lives, and not vice versa. What comes first, however, is that we understand how they work.

“Society is composed of persons who cannot design, build, repair, or even operate most of the devices upon which their lives depend…In the complexity of this world people are confronted with extraordinary events and functions that are literally unintelligible to them. They are unable to give an adequate explanation of man-made phenomena in their immediate experience. They are unable to form a coherent, rational picture of the whole. Under the circumstances, all persons do, and indeed must, accept a great number of things on faith…Their way of understanding is basically religious, rather than scientific; only a small portion of one’s everyday experience in the technological society can be made scientific…”

God, Human, Animal, Machine, Meghan O’Gieblyn (2017)

My most recent read. O’Gieblyn comes at the question of transhumanism and accelerating technology as someone who has moved past the Christian faith. She finds that technology is asking many of the same questions as the world she left. I wrote a little about how O’Gieblyn describes our search for the “soul” in machines that she sees as being devoid of them.

I found the book to be a rare rigorous philosophical exploration of very modern-day happenings. It left me with more questions than answers. This is my most recent read, and I think I’ll have to return to it a few more times before I understand it in depth. But I am quite certain that I enjoyed it, and will be reading it many times over.

The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard (1958)

A strange book. Somewhere between poetry and non-fiction. When I found it outside, on a sidewalk near my house, it was dog-eared and had three different pens—and what I think were distinct handwritings—taken to it. I would recommend to anyone thinking about the home.

Bachelard considers the home as one of the first influences on a person’s mind, “a body of images that give mankind proof or illusion of stability.” There is fear in the attic and in the cellar; corners where we can go and hide; the attic where we set our ambitions; the house of the future—the dream house, which must always be delayed, something we are grasping towards. It is all written as if everything Bachelard considers is fact. I tore through it in two days while visiting my parents, and felt I had many epiphanies about my life; but, months later, I’m finding that the notes don’t work as well as what I get in other non-fiction books, most of them are quite strange, and I think I’ve understood that this book is more symbol than fact.

Working in Public, Nadia Eghbal (2018)

I read Eghbal’s book on open-source software a few years ago, but my head was elsewhere at the time. I re-read it again, and found it very illuminating.

Eghbal spent several years interviewing developers at GitHub, the Microsoft-owned platform (2018) where open-source code is hosted. She writes about the roots of online “anarchist” open-source culture, which was hosted across little projects and scaffolded itself on beliefs like decentralization and free information. This culture shifted onto the private platform GitHub, which made it easier to connect across communities. GitHub grew into a veritable commons; until, Eghbal writes, it began to deteriorate.

Developers stopped contributing as much to projects, preferring to use the free code like a free service—like they were consumers of a free social media app. A handful of coders were left maintaining the project for no reward outside of popularity. As projects grew unwieldy and more difficult, the incentives shrank. Only a few were what Eghbal describes as “federations,” projects that continue to see contributions and new people join.

This book is a really interesting study of the digital commons—and whether that is even something that can be aspired to on the internet, where there is no overarching government, which means there is technically no public. I was reminded of Laurel Schwulst, who is starting to think about what the PBS (public broadcasting service) of the internet could look like.

Cyberfeminism Index, Mindy Seu (2022)

Not a traditional book, more like a phonebook (also a website). A compendium of cyberfeminist projects that started as an Excel sheet sent out by Seu in 2019, because she wanted to create an index of these works that had started to populate the internet in the early 90s, imagining how technology could liberate feminism, and vice versa.

This has been an interesting book to keep by my desk and flip through now and then to find relics like a 1997 Hari Kunzru interview with Donna Haraway or a 1992 sci-fi novel in which a developer turns herself into an android. I felt, for a little while, that I was looking at these projects as toys, novelties that wouldn’t do much to change culture or the internet we live in. One theory that has emerged for me recently is that the answer might lie in local networks that connect communities, and not the world at large.

If It’s Monday It Must Be Madurai, Srinath Perur (2013)

A very funny collection of essays worth reading. Especially for those whose family members are fond of group tours.

Perur joins ten different tours that depart from Bengaluru to various cities around India, as well as several other countries. The stories chronicle how fellow travelers act on their trips. I’m more used to travel writing in the tenor of solo reflection, the visited location acting as a mirror to the self, but in a world where things are less distant, this genre has lost its appeal for me. So this was a nice replacement.

My favorite essay is one in which Perur ends up in Uzbekistan and realizes that most of the group is there to have sex in a more liberal environment than India. This becomes even more absurd when he realizes that the only cultural nodes most travelers share with those around them are from Hindi films, which were popular in the USSR.

Annie Ernaux, Shame (1997)

A book for writers who engage with memory. A book for anyone, really, who finds that they are distinct from the world they grew up in. Ernaux, rest in peace (I was told, after publishing this, that I fell for some hoax and that she still lives on and well, disregard), is one of the few who can write memoir with a steady hand. My favorite of her books.

It’s a short book in which she turns over a single, violent memory that occurs in her childhood home in Normandy. The memory, after examination, starts to reflect the working class milieu she was brought up in, and how it influences the shame she carries with her. She ties her upbringing, even, to her writing style.

“I shall never experience the pleasure of juggling with metaphors or indulging in stylistic play…there were hardly any words for describing emotion—I was put straight (disenchantment), I was black as thunder (discontent). It grieved me could mean being sorry to leave food on one’s plate or being sad at losing one’s sweetheart. And of course to breathe disaster.”

Three short stories

Houhynnm, Andre Alexis, The New Yorker

Slow Clap, Amy Zhang, Joyland

The Nose, Nikolai Gogol

—To be read once a year. One of the best stories ever written about noses. Maybe one of the best stories ever written, period.

Thanks for the recommendations!

Adding Perur's collection to my reading lost now - sounds excellent!!